New insights on surge, forecasting

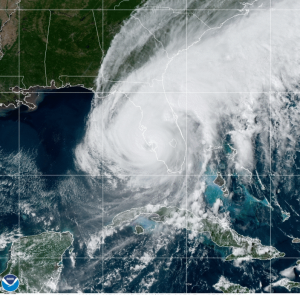

A satellite view of Hurricane Ian after making landfall on September 30, 2022 in Lee County, Florida. Courtesy, NOAA

Hurricane Ian has officially become the costliest Florida hurricane ever, causing twice as much damage as Hurricane Andrew did 30 years ago. That’s part of the findings in the National Hurricane Center’s Tropical Cyclone Report for Hurricane Ian released last week. Ian caused an estimated $109.5 billion in damage in Florida, including insured and uninsured losses. Compare that to Andrew’s $54 billion (adjusted to today’s dollars) back in 1992. Total Ian damage is $112.9 billion across the Southeast U.S., making it the third costliest storm in the nation’s history.

The high-end Category 4 storm that made landfall near Ft. Myers on September 28, 2022 was responsible for 66 direct deaths and another 90 indirect deaths in Florida from the catastrophic storm surge, damaging winds, and historic freshwater flooding across much of central and northern Florida. The report provides some excellent detail on damage, issues with the forecast track, and which hurricane model was best.

Damage: In Fort Myers Beach alone, an estimated 900 structures were totally destroyed and 2,200 were damaged. Many of those were from storm surge of 10-15 feet, much greater than the originally forecast 7 foot surge. In the broader Lee County, at least 52,514 structures were impacted, of which 5,369 were destroyed and 14,245 received major damage.

Ian dumped 10-20 inches of rain across parts of central and eastern Florida, with the highest amount of 27 inches in Grove City, northwest of Ft. Myers. The resulting widespread historic freshwater flooding caused destruction and significant damage to many structures and roadways, leading to over 250 water rescues. In Volusia County, 40 buildings were destroyed, and 1,378 structures were damaged. Ian damaged an estimated 4,100 structures in Osceola County and 1,656 structures in Seminole County. State agriculture officials note an estimated $1.1 to $1.8 billion in losses due to flooding and wind damage to crops and infrastructure.

Series of still images and the approximate local times from a remote camera that recorded a timelapse video of storm surge inundation and destruction in Fort Myers Beach. Credit: Max Olson

Forecast Track: There was some criticism after landfall that the original forecast track, which put Ian making landfall farther north in the Tampa Bay area, was in error and left less time for Southwest Florida to prepare for a direct hit. The report found that errors in predicting the storm’s path were not out of the ordinary. “The average official track forecast errors were lower than the mean official errors for the previous 5-yr period” as the storm developed, the report noted.

Best/Worst Models: Consensus models, which combine data from a number of hurricane computer models, outperformed the National Hurricane Center’s forecasts at some points. The best-performing model for short-term forecasts was the Florida State University Superensemble. The model with the greatest track errors was the Canadian model, the report said.

“Examination of the individual official forecasts revealed the cross-track error to be the largest source of error with a consistent westward bias noted,” the report found. “While the left-of-track bias made forecasting the exact landfall location of the Ian in southwestern Florida difficult, the forecast track cone of uncertainty did contain the landfall location for all advisory cycles. In general, storms that parallel a coastline tend to be more challenging to predict because a small change in heading can cause large differences in the landfall location. Ian was an example of this particular challenge.”

LMA Newsletter of 4-10-23