Plus, oyster harvesting returns to Apalachicola Bay

Sargassum swells could swamp Florida beaches this year, the warm return to tradition hits commercial oyster fishers in Apalachicola Bay, and proposed offshore fish farms off Florida’s Gulf Coast are causing a stir. It’s all in this week’s Environmental and Engineering Digest.

Sargassum swells could swamp Florida beaches this year, the warm return to tradition hits commercial oyster fishers in Apalachicola Bay, and proposed offshore fish farms off Florida’s Gulf Coast are causing a stir. It’s all in this week’s Environmental and Engineering Digest.

Seaweed on the beach in Alligator Point, FL, September 1, 2024

Sargassum Swells: The familiar sight of Sargassum – stinky masses of floating seaweed that wash up on beaches and are an eyesore and economic hinderance − might be the worst seen this year, say researchers. Using satellite data to measure the biomass, USF researcher Huanmin Hu and team have found that there are two distinct swaths of sargassum, larger than 75% of previous years, and both still growing. Large bloom fluctuations started back in 2011 when the seaweed bloomed far further south than its usual Sargasso Sea stomping grounds, forming a phenomenon called the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, the “largest interconnected floating biome on Earth,” according to a study from the Max Planck Institute. While scientists have several ideas on what could be causing an influx of nitrogen that supercharges the sargassum, one thing’s for certain: this bloom will cost billions of dollars. A study by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution estimates that via dampened tourism, disrupted fishing, and damage to coastal infrastructure, Florida could lose out big time. And just like some of our other recurring ecological problems, the seaweed only seems to be getting worse.

Oystermen out on Apalachicola Bay. Courtesy, Stan Kirkland, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Return of the Oysters: As we reported back in November, Apalachicola Bay, Florida’s historic oyster harvesting hotspot, is back open for business after years of collapse and a five-year-long complete shutdown. The allotted two-month harvesting season opened on New Year’s Day and brought with it remembrance of great tradition for many families in the Bay, who were unsure they would ever return to their old ways of life. “10 minutes after we opened on the 2nd… everybody [was] waiting for the oyster guy to come through the door, and he walked in and everybody cheered,” said Hole in the Wall raw bar owner Cliff Babbey to the Tallahassee Democrat. “It’s a tremendous morale boost for the area. Tremendous.” Even though the 31-bag limit per person on the brief harvest season isn’t enough to make a full-time living, it’s about something deeper than the money for the Apalachicola old-timers. Many of the locals reminisce about when oyster processing plants lined Route 98, providing hundreds of jobs, before the combined human efforts of dams, reservoirs, and dredging changed the salinity levels in the bay and thereby the presence and health of the oysters. While the briny waters will perhaps never again provide the 10% of the nation’s oysters like they once did, for the next several weeks the community can find its way back to a cultural cornerstone found just a few feet beneath the water’s surface.

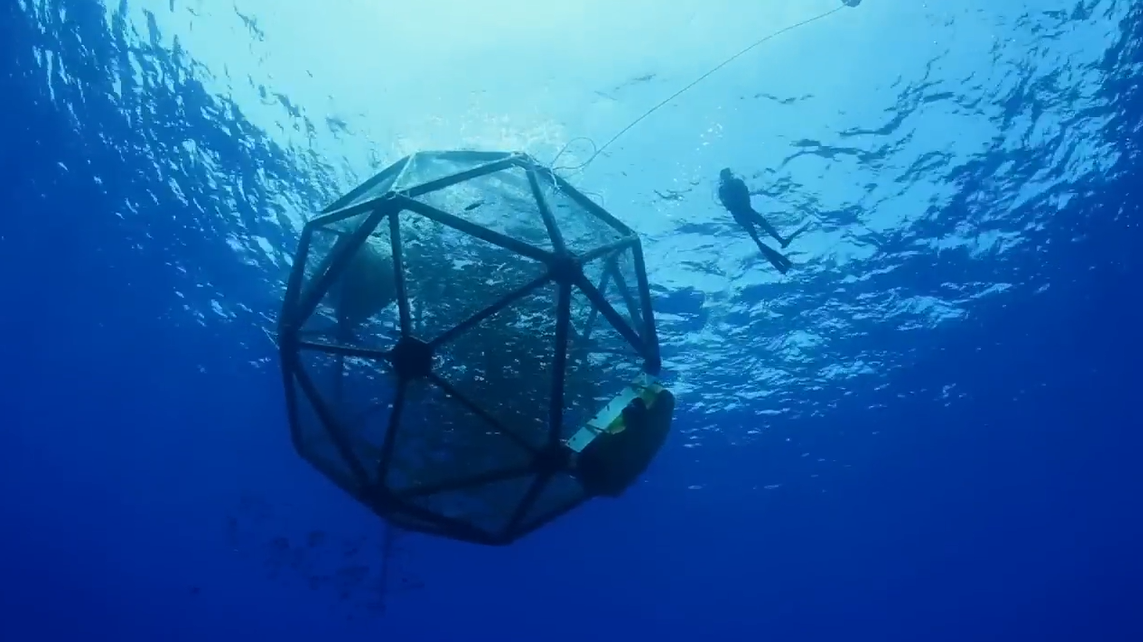

An offshore aquaculture trial around Hawaii. Courtesy, Ocean Era

Florida Offshore Fish Farming: A proposal to place huge fish farms in the federal waters off Florida’s Gulf Coast has brought a healthy debate over the ecological balance in the area, as reported by the Food and Environment Reporting Network. Americans now eat more farmed seafood than wild-caught and most is imported. Proponents of the farms say this brings food to the table and reduces reliance on foreign markets, all with less environmental damage than traditional methods. “All of the evidence confirms that if you do this in deep enough water with a bare sand bottom and with some reasonable water movement, you have no significant environmental impact and often no measurable environmental impact at all,” said Anthony Simms, founder and CEO of Ocean Era, a Hawaii-based company seeking approval for one of these farms. But folks who have lived near these farms tell a different story – one of damaged local waters and coastlines. “It makes a few jobs but the jobs don’t justify the environmental damage,” said Melvin Jackman, who lives near salmon farms in Newfoundland. “It simply doesn’t. I want my grandkids to walk on a clean shore … think twice before they put that in your area.”

See you on the trail,

Lisa