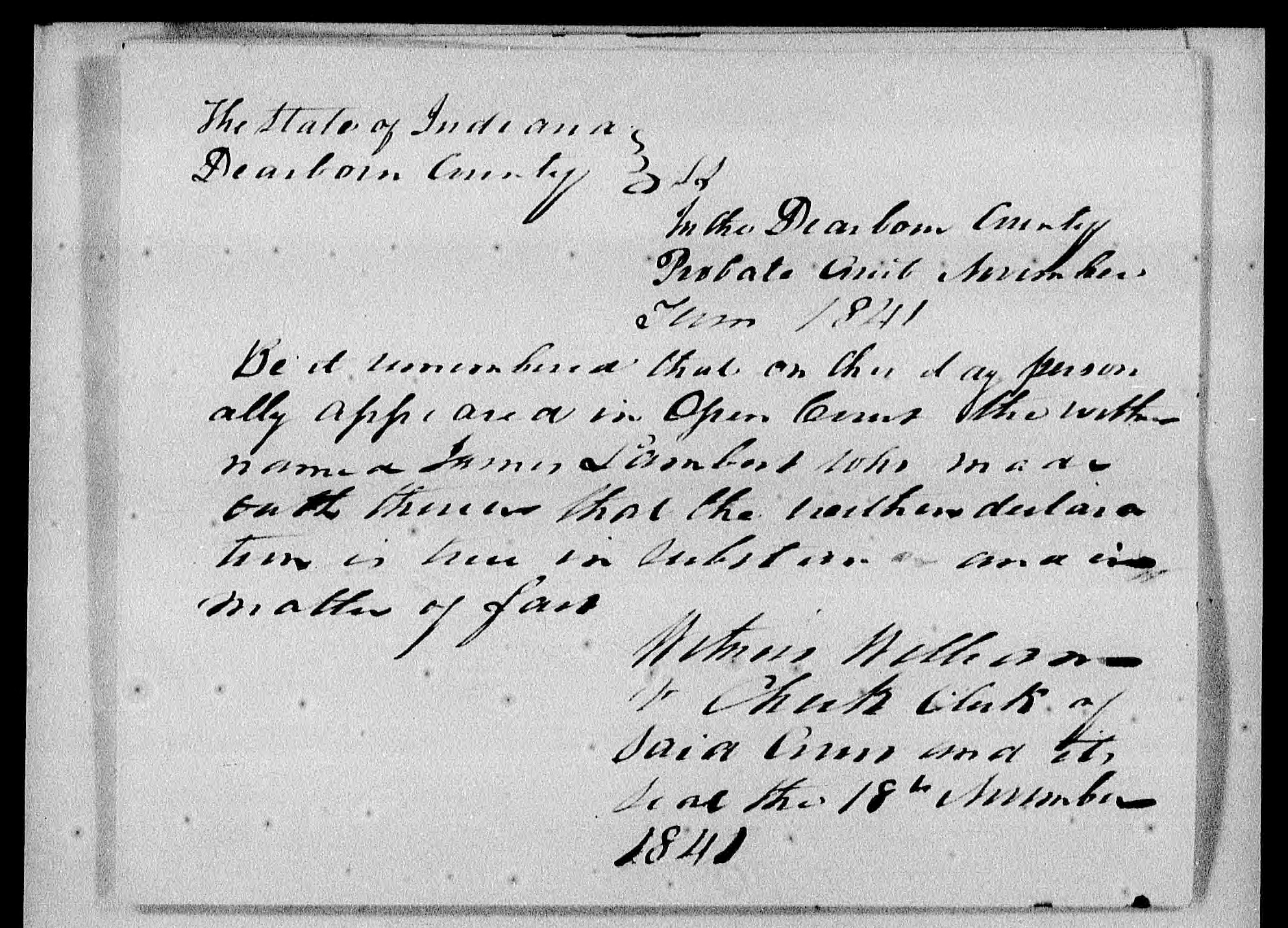

Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application for James Lambert, Virginia. Source: National Archives

Many things are lost to the conveniences of the modern age, and cursive handwriting is no exception. For recent younger generations who did not learn cursive in school, the script can be more like a foreign language than our more standardized lettering – enough so that the National Archives have taken to the internet to recruit those who can transcribe cursive historical documents to improve accessibility.

In an effort to bring history to more hands, the National Archive has opened free sign-ups for its “Citizen Archivist” program online for anyone with an internet connection. With countless documents dating back more than 200 years, each handwritten letter, note, or other document is a window to the past, that some people cannot see through – not without a little help. While the Archives digitize tens of millions of documents each year, its AI technology seems to have a little more difficulty with cursive, which is where the volunteers come in. Transcribing these pages means easier access, categorizing, and analysis of our history, benefitting everyone from scholars to linguists to those with just a burning curiosity about the past. So far, over 5,000 transcribers have joined the program.

But the jobs don’t stop there – there is something for everyone to do to help bring history forward, even those who cannot read cursive themselves. The National Archives is also accepting help organizing and tagging already transcribed documents and the work schedule can be as flexible as need be. Some people find 30 minutes a week to help with the project; others, like retiree Alex Smith, have transcribed more than 100,000 documents in their time with the program. Their hard work will help us gleam bits and pieces from the fabric of our past, the lives of those who brought us to where we are.

Currently, missions for the project include Revolutionary War pension files and employee contracts from 1866 to 1870 in partnership with the National Park Service (NPS). Included documents connect a web of more than 80,000 veterans and their widows and could help us enrich our own lives through their experiences. “The pensions are revealing the stunning—frequently heartbreaking and sometimes funny—complexity, nuance and previously unknown details about the American Revolution and the nation in the decades after,” said Joanne Blacoe, an interpretation planner for the NPS, in a statement. “It’s rich content that will benefit parks and inspire artists, researchers and families connecting to ancestors.”

Converting these documents to plainer letters and cultivating a sense of connection is great – but it begs the question, does teaching cursive still have a place in our schools like it has a place in our collective past? While keyboards and computer screens have taken center stage in most of our lives, perhaps it should not come at the cost of penmanship. States like California and Kentucky have recently mandated cursive instruction in the classroom in an effort to conserve this tool of the English language. To some, it’s a fancy scrawl across the page. To others, it’s a link to the lives of those who laid the groundwork for our own.

See you on the trail,

Lisa