As Hurricane Dorian bears down on Florida, two reports that examined damage from last fall’s Hurricane Michael have mixed reviews on building construction in Florida’s Panhandle. While newer homes built after the 2002 Florida Building Code was enacted suffered less structural damage than older homes, the roof cover loss and siding damage was just as common in the newer structures. In fact, almost two-thirds of those newer buildings built after the code went into effect had some roof loss from Michael’s high winds.

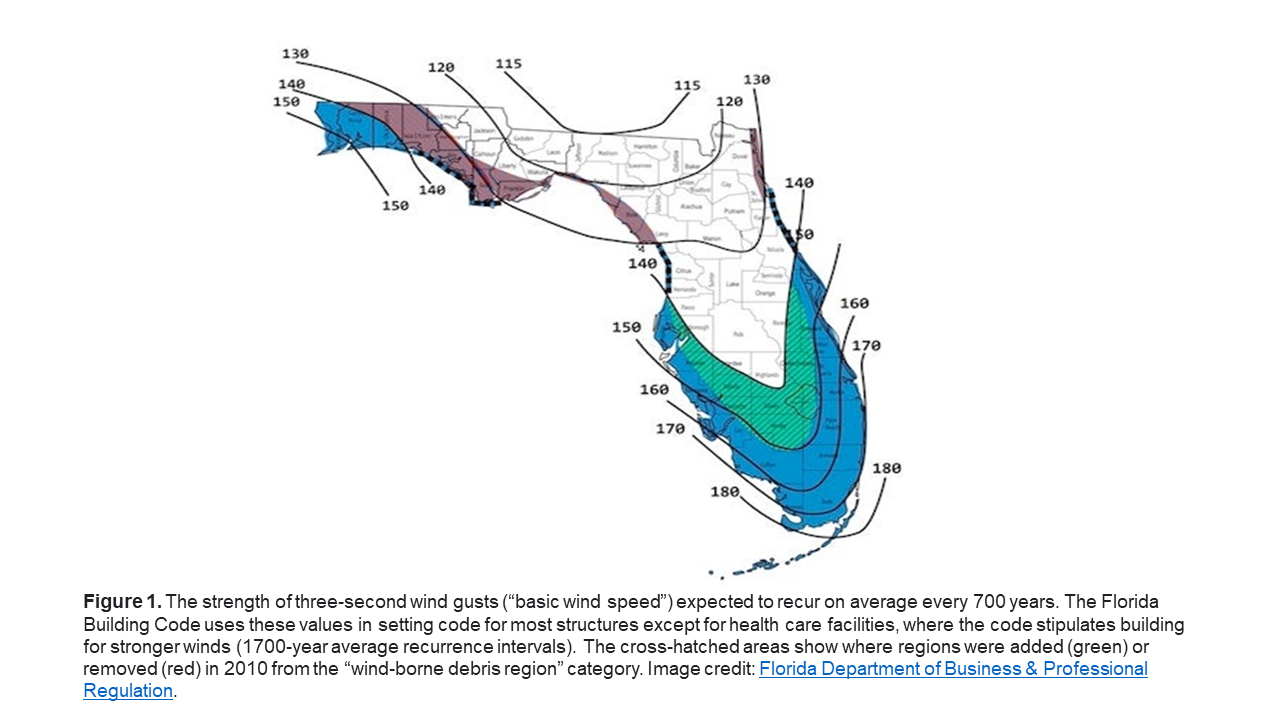

While Florida is known for its tough building code, few know that the maximum wind standards of materials and methods in the code vary depending on which part of the state you live. Miami-Dade County, where Hurricane Andrew struck in 1992, has the toughest wind standards. But the Florida Panhandle, where Hurricane Michael’s Cat 5 winds struck in 2018, has among the weakest wind standards. Why? Just how vulnerable are homes throughout Florida? And what can be done to strengthen them?

Host Lisa Miller, a former deputy insurance commissioner asks noted television meteorologist and hurricane expert Bryan Norcross and Cindy Shaw, a forensic engineer with Haag Engineering Services.

Bryan Norcross, Hurricane Specialist, WPLG-TV Local 10 News

Cindy Shaw, Senior Engineer and Southeast Regional Manager, Haag Engineering Services

Show Notes

Hurricane Michael struck the Panhandle as a Category 5 storm, the fourth in U.S. history, with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph and a 15-foot storm surge. 43 people died in the storm and its aftermath. Total damages are estimated to climb to $25 billion.

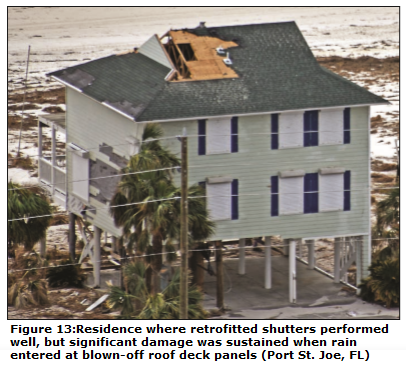

A University of Florida Engineering School report prepared for the Florida Building Commission examined both wind and storm surge damages from Hurricane Michael. It found that roof cover loss was the most common type of structural failure, even with wind exposures below the building code’s threshold.

“Structural damage was predominantly experienced by older (pre-2002) structures, while newer structures generally experienced no more than roof cover and wall cladding loss. However, roof cover and wall cladding damage was still commonly observed even in newer structures,” according to the report. Almost two-thirds of buildings built after the code went into effect had some roof cover loss.

Another report from the Structural Extreme Event Reconnaissance Network had similar findings.

Although Florida is recognized as having the toughest building codes in the nation, they vary by wind standards, depending on the area of Florida. In the Panhandle, where Michael struck, those wind standards are among the weakest in the state at 130 mph at the coast and 120 mph slightly inland. In Miami-Dade and Broward Counties, the standards are the strongest at 180 mph at the coast and 170 mph inland.

Cindy Shaw is a Senior Engineer and Southeast Regional Manager for Haag Engineering Services, a global forensic engineering and consulting firm. In her review of the reports, Shaw said she noted improvement in homes built after the enactment of the 2002 Florida Building Code, but performance varied a lot, even among similar homes. Homes built above code standards performed best.

Cindy Shaw is a Senior Engineer and Southeast Regional Manager for Haag Engineering Services, a global forensic engineering and consulting firm. In her review of the reports, Shaw said she noted improvement in homes built after the enactment of the 2002 Florida Building Code, but performance varied a lot, even among similar homes. Homes built above code standards performed best.

“Finishing materials installations varied within a single residence and that led to wind damage. Roofing that was to a higher code than a garage door led to vulnerabilities and failures in the overall structure,” said Shaw, a 20 year veteran of structural inspections.

“It was tremendously frustrating to see the damage from Hurricane Michael because we lived this already,” said Bryan Norcross, Hurricane Specialist for WPLG-TV, Local 10 News in Miami. He is known for his 23-hour on-air marathon during and after Hurricane Andrew struck South Florida. Andrew was the last Cat-5 storm to hit Florida before Michael.

“Something failed. The roof might have been good, but the windows or the front door or the garage door wasn’t, and that lead to a cascade of failure once the home’s envelope was breeched. Our tougher building code in South Florida post-Andrew, ensures the entire house is secure by all its components meeting the same standard,” said Norcross. “The building code was somewhat intentionally made less strong in the eastern Panhandle than even the western Panhandle for no rational meteorological reason.”

The problem with the current Florida Building Code and its varying wind standards, said Shaw, is that it doesn’t deal with areas of the state that have had significant hurricanes, whose wind standards don’t match their historical experience. Shaw said those need further refinement. She noted that Florida’s code for existing structures, which covers buildings being updated, is a good example of progressively refined codes that work well.

So what would Shaw and Norcross advise the Florida Building Commission on potential changes post-Hurricane Michael?

So what would Shaw and Norcross advise the Florida Building Commission on potential changes post-Hurricane Michael?

Shaw, who specializes in examining new building materials and methods in the Florida Building Code in between hurricanes, said the design wind pressures that exist as standards need to be less arbitrary and political and instead correlate to the reality of the coastal regions. Improved code enforcement is needed, too.

“It’s not that we expect to have no damage when we have a Category 5 hurricane, but we would like to not have catastrophic damage. We would like to not have loss of life. We would like the homes to still be livable. And with regard to Hurricane Michael and up in the Panhandle, we failed on all three of those fronts,” said Shaw.

Norcross agreed. “We have this high-velocity wind zone here in Southeast Florida, for no rational reason does it stop at the Broward County lines. There’s just no meteorological reason why you couldn’t have a Category 5 hurricane strike any part of the state of Florida and have a Category 3 or 4 hurricane go all the way across the state. You don’t even have to think about it as a meteorologist, you just have to look in the history book to see examples….Ironically, the Panhandle is especially vulnerable to strong hurricanes,” he said.

As for the higher cost of construction that comes with a stronger code, Norcross and Shaw agreed that there are other places in the building where cost savings could be achieved and channeled to build a safer, more durable house. “It’s just too easy to do it all the way right, than to do it halfway,” said Shaw.

“The real challenge for builders and the real resistance here, is the inspection process,” said Norcross. “It is a pain in the neck to do anything here in South Florida…the issue is to create an inspection system that is as efficient and simple as it can be.”

Host Lisa Miller, a former Florida deputy insurance commissioner, noted that building better should lead to lower property insurance costs as well. “Hurricanes and other catastrophes don’t know or care who is insured or not and as we’ve learned, don’t necessarily follow historical patterns – including those on which we base risk.”

Links and Resources Mentioned in This Episode:

Investigation of buildings damaged by Hurricane Michael (The University of Florida Engineering School of Sustainable Infrastructure and Environment, prepared for the Florida Building Commission, June 10, 2019)

Hurricane Michael: Field Assessment Team Early Access Reconnaissance Report (from Structural Extreme Event Reconnaissance Network, October 25, 2018)

Pitfalls in Mitigating Risk (LMA Newsletter of 8-26-19)

Florida Building Commission Wind Maps

Cities Where Hurricanes Would Cause the Most Damage (24/7 Wall Street, July 31, 2019)

** The Listener Call-In Line for your recorded questions and comments to air in future episodes is 850-388-8002 or you may send email to [email protected] **